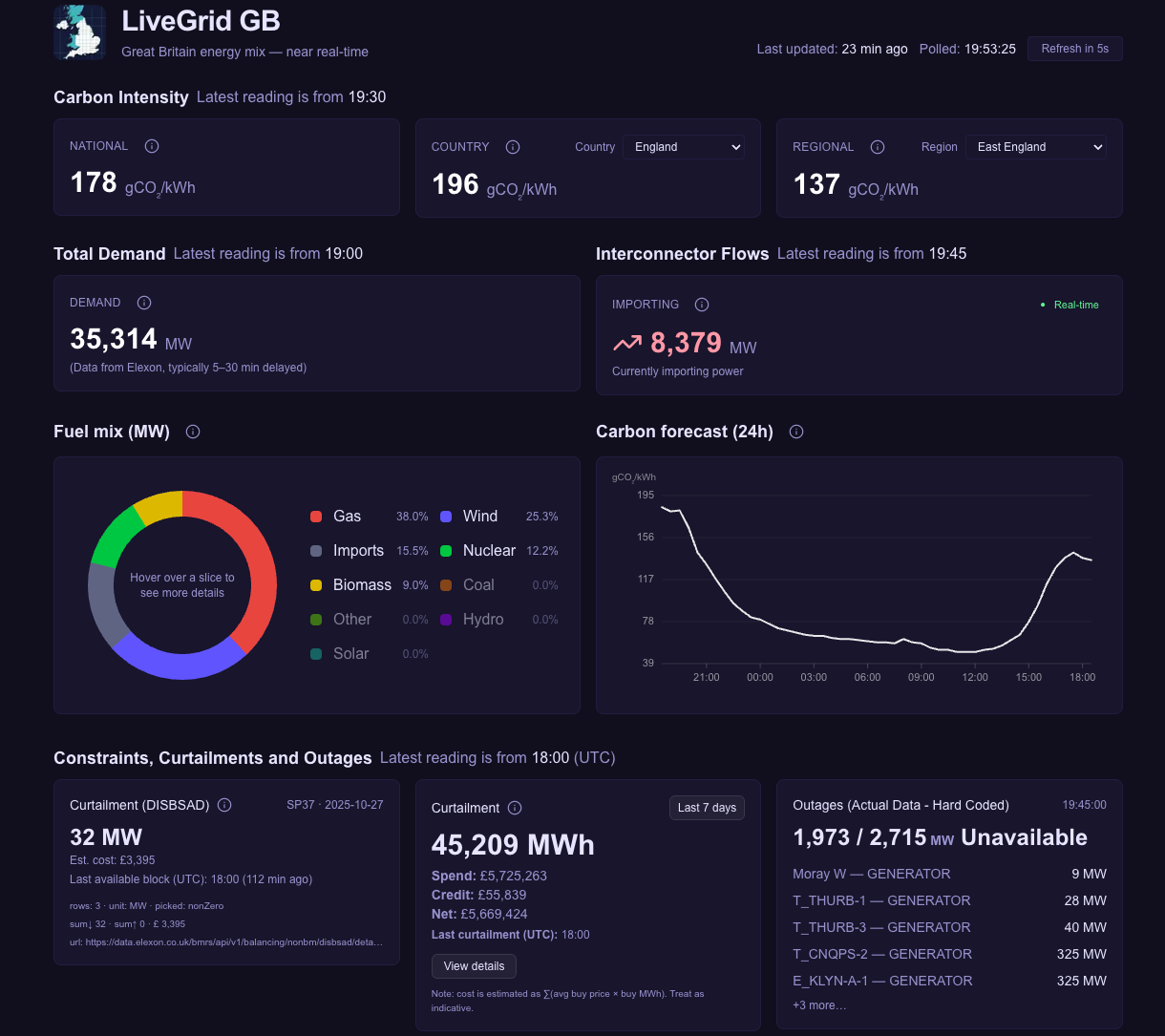

When I first started building LiveGrid GB, my goal was simple — to visualise how Britain’s energy system works in near real-time. I wanted to see where our electricity came from, how much of it was renewable, and how it all balanced across regions. What began in my head as a simple and coding challenge, quickly became something else: a window into how complex, inefficient, and sometimes illogical our national grid can be.

Over the past ten days, while working on integrating Constraints, Curtailments, and Outages into the app. I'm still refining the Outages side, but the curtailment data alone has been enough to stop me in my tracks. What I’ve learned is both fascinating and frustrating, it says a lot about how our energy system really works behind the scenes; that clean energy doesn't always mean clean decisions, and that sometimes we spend millions to waste it.

Understanding Curtailment: The Hidden Cost of Renewable Energy

Curtailment sounds technical, but the idea is simple: it’s when we turn off renewable energy. Wind farms, solar arrays, and hydro plants are sometimes instructed to reduce or completely stop generating electricity, even when conditions are perfect. It isn’t because the energy isn’t needed — it’s because the grid can’t handle it.

Our grid was built decades ago for predictable fossil-fuel generation, not for variable renewables. The main culprits are out infrastructure and imbalance: Scotland, for instance, produces far more wind power than it can use, while Southern England consumes more than it generates. Because the transmission capacity between the two are limited, the grid operator (National Grid ESO) has no other option but to tell certain generators to switch shut down.

And when they do, the operators are compensated — paid for the electricity they could have generated. In other words, we pay them to do nothing.

Curtailment Costs: The Bill No One Talks About

Few people realise how expensive this practice really is. On particularly windy days, the cost of curtailment can run into the millions per day. Over a full year, the total cost is in the hundreds of millions of pounds, all of which filters back into our energy bills and taxes.

The logic is grimly circular: instead of investing those funds our grid and strengthening our transmission lines, or investing in battery storage, we spend them maintaining the status quo. The system keeps paying for its own inefficiency.

There is also a painful irony here; on days where we are curtailing wind power in the North, we're often also importing electricy from abroad - sometimes which has been generatyed by fossil fuels - to meet the demand in the South. We are paying to waste clean energy, while paying again to buy dirty energy.

This cycle doesn't just cost money; it costs progess.

When Prices and Volumes Go Negative

If you’ve ever looked at wholesale energy prices and thought they made no sense, you’re not wrong — they often don’t.

Occasionally, both prices and volumes go negative. That means generators or buyers are paying to move energy rather than earning from it. It happens because shutting down turbines or balancing supply and demand on short notice can be more expensive than simply accepting a financial loss.

For example, looking at data from 26 October 2025 (Settlement Period 48), the grid recorded both buying and selling activity with contradictory price and volume patterns:

"settlementDate": "2025-10-26",

"settlementPeriod": 48,

"startTime": "2025-10-26T22:30:00Z",

"buyActionCount": 1,

"sellActionCount": 13,

"buyPriceMinimum": -0.51,

"buyPriceMaximum": -0.51,

"buyPriceAverage": -0.51,

"sellPriceMinimum": 0.05,

"sellPriceMaximum": 4.24,

"sellPriceAverage": 1.186153,

"buyVolumeTotal": -8.5,

"sellVolumeTotal": -491.5,

"netVolume": -500Here, the grid was effectively buying electricity at a negative price and volume, while simultaneously selling electricity at a positive price but negative volume.

That means we were paying to buy less and paying again to sell less. It’s a paradoxical situation that arises from how the balancing mechanism is structured — when the grid needs to rapidly stabilise itself, it often resorts to financial signals that seem illogical on the surface. And this isn’t just a one-off glitch. These patterns can appear on both sides of the market — for buying and selling electricity alike — reflecting how delicate and reactive the system has become.

When both prices and volumes turn negative, it exposes the underlying inefficiency of a grid built for predictability, not volatility; one which was built for fossil fuels, now struggling to adapt to the flexibility and variability of renewables. What looks like a stable set of transactions on paper can actually represent the grid paying to avoid using energy — a stark illustration of just how misaligned our infrastructure and market mechanisms have become.

Why the Government Hasn't Fixed It

Given the scale of these costs, it’s reasonable to ask: why hasn’t the government stepped in?

The truth is that the current system, however wasteful, still “works” on paper. Energy keeps flowing, the grid remains stable, and the market settles every day. But that stability comes at a massive hidden price: the taxpayer-funded compensation paid out through curtailment. The infrastructure problems at the heart of this — limited grid throughput and the lack of large-scale battery storage — fall into a grey area of responsibility. The government doesn’t directly own most of the transmission network, nor the generation or storage facilities. That makes it easy to treat the issue as market inefficiency rather than a policy failure — but the truth is, the market isn’t built to fix it. When every player is compensated for inefficiency, no one has the incentive to change.

Expanding grid capacity or deploying battery farms requires long-term investment and clear regulation. Without government pressure, energy companies simply follow the existing compensation model — one that pays them whether they generate power or not. Battery storage, in particular, should be the bridge between renewable generation and grid stability. It would allow excess energy to be captured instead of wasted, ensuring consistent income for producers and cheaper energy for consumers. But because it disrupts the current flow of curtailment payments, it doesn’t naturally fit within the short-term market logic that dominates today’s system.

In short, the lack of government intervention isn’t an accident — it’s the byproduct of a market designed for short-term balancing, not long-term efficiency. And until policy catches up with technology, we’ll keep paying the price for that imbalance. I'm not arguing for government should step in by nationalising assets, but by reforming market incentives and directing investment toward grid throughput and storage capacity, simply reworking curtailment compensation so that efficiency becomes more profitable than inefficiency is one solution.

Insights From Building LiveGrid GB

Working directly with real curtailment and constrain data has been eye-opening. What surprised me the most isn't just the amount we are spending, even though this was a shock when I first saw a day in which we spent more than a million pounds in curtailing energy - it's how misleading the data can be. Across different sources, I've seen both positive and negative prices, and volumes appear simultaneously, for both buying and selling energy. Sometimes what seems as a credit to the system is actually a cost; other times, the data revewrses entirely. It feels almost deliberately confusing, as if it was designed to make it harder for the average person to understand what's really happening.

That's, in part, why I am building the LiveGrid GB site the way I am. To simplify and visualise the information more clearly. Seeing it in contect changes how you think about the grid. It's not just numbers, it's a map of decision-making, incentives, and inefficiencies that ripple through the entire system.

Looking Ahead: What If the Grid Warked Smarted?

Imagine a grid where curtailment was the exception, not the norm; where every surplus megawatt is stored, redirected, or sold intelligently. It's entirely possible. With smarter forcasting, AI-driven balancing, and most imprtantly, a more modern-infrastructure, we could dramatically reduce the curtailment costs while improving reliability. The frustrating truth is that we already spend enough to make this vision of the future a reality, we just spend it in the wrong places.

Transparency and technology are the first steps. By opening up this data and helping people understand it, we can start asking better questions of the policymakers and industry leaders. The more people that see what's actually happening, the harder it becomes to ignore.